Category

with Critical Mass Performance GroupCreated, directed, produced by:

Nancy Keystone 1997-2000

Created in collaboration with:

Critical Mass Performance Group

World Premiere Los Angeles, 2000

Named one of the “10 Best” Productions for 2000, by Los Angeles Times, nominated for 4 LA Weekly awards (Best Production, Director, Ensemble, Choreographer-winner).

Performed as a work-in-progress at ASK Theater Projects’ Common Ground Festival, The Getty Center, Lankershim Arts Center.

THE COMPANY

Natasha Basley, Russell Edge, Sarah Gossage, Joseph Grimm, Christopher Kelley

Eric Marx, Kathryn Miller Kelley, Joe Palmiotti, Candace Reid, John Prosky, Valerie Spencer, Miranda Viscoli

scenic design by Nancy Keystone

original music & sound design by Randy Tico

lighting design by Daniel Ionazzi

costume design by Lee Kartis

Reviews

“…The tone is like a sledgehammer pounding an anvil. When sparks fly, they are the words of the poems…THE AKHMATOVA PROJECT is a labor of devotion whose integrity resonates from the stage…an emotional cry, a tone poem, an ode to the vigor of the crafted word, and to the people who craft it.”

—Steven Leigh-Morris, LA WEEKLY, 2000

“…dazzling epic movement piece…a riveting narrative…stunning choreography and visual tables…intoxicating milieu…”

—Miriam Jacobson, LA WEEKLY, 2000

“…lyrical…intense…elegant and spare…”

—Jana J. Monji, LA TIMES, 2000

“THE AKHMATOVA PROJECT is a numinous study of the struggle of the artist against the state and the often appalling costs of that struggle. Theater doesn’t get any more compelling or meaningful than this.”

—T.S. Kerrigan, AMERICAN REPORTER, 2000

“…the final scene is more like a vacuum struggling against the audience’s soul than a culmination or conclusion. I literally felt my soul sucked out of my body in that last moment–and no one, no thing, no single event has ever done that to me.”

—Scott Schaeffer, Editor, MUNDANE BEHAVIOR, online

L.A. WEEKLY

“Seeing Red “

(Feature Article 3/31—4/6, 2000)

by Steven Leigh Morris

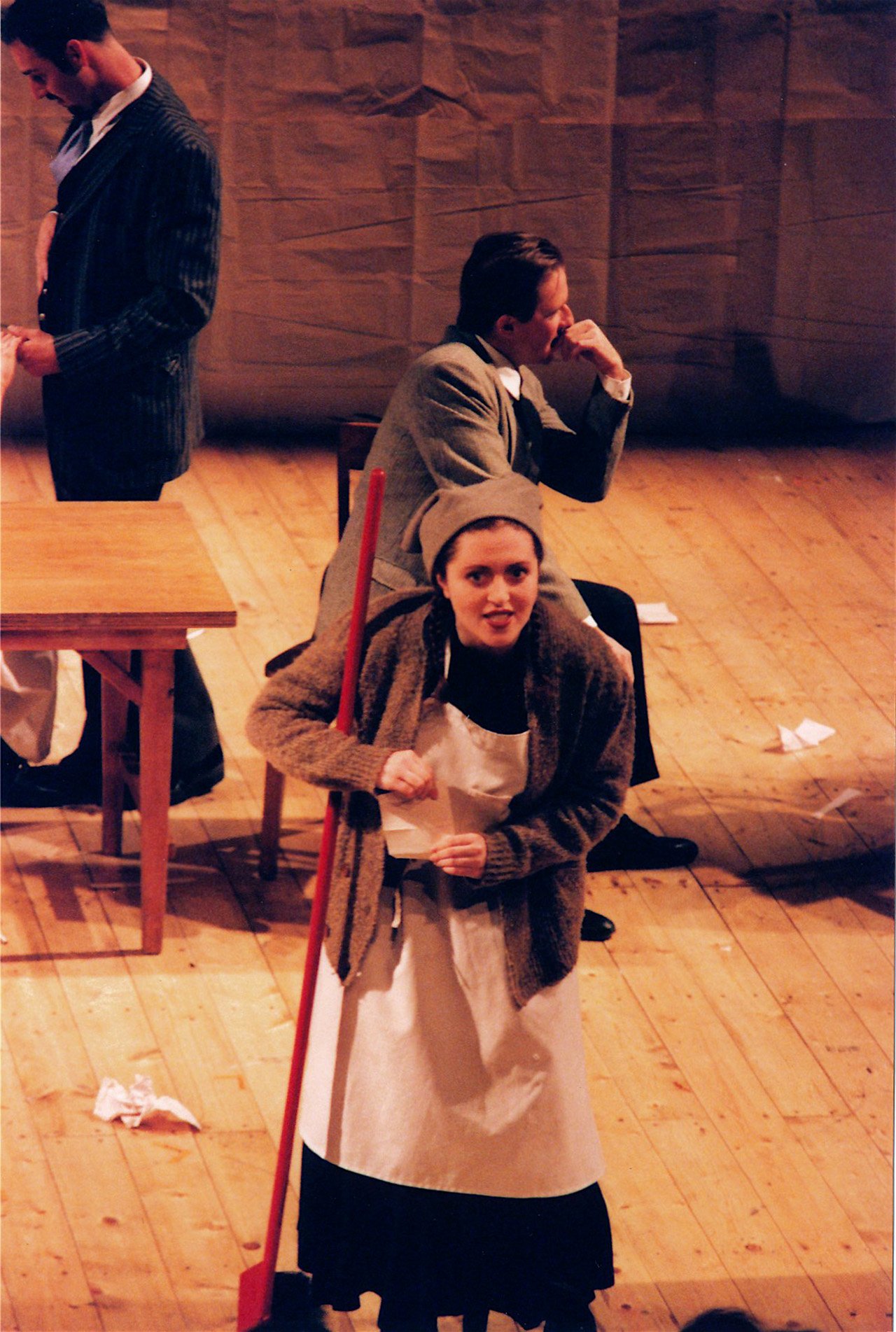

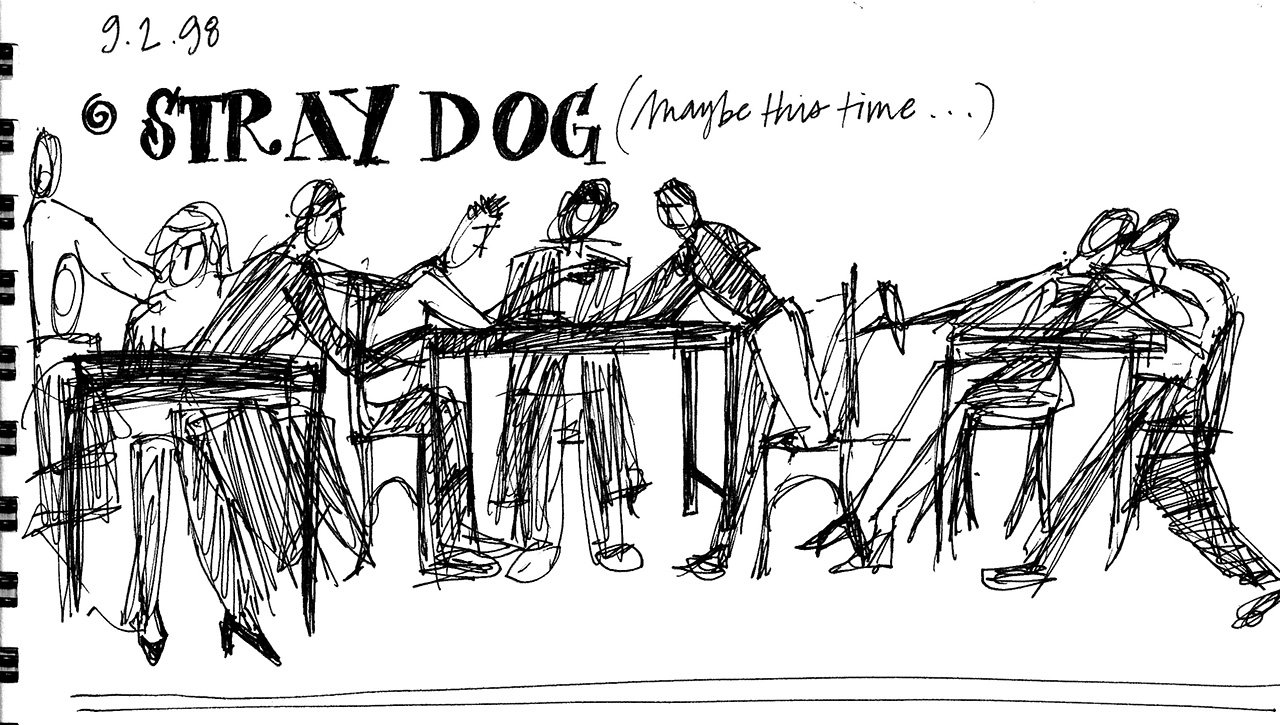

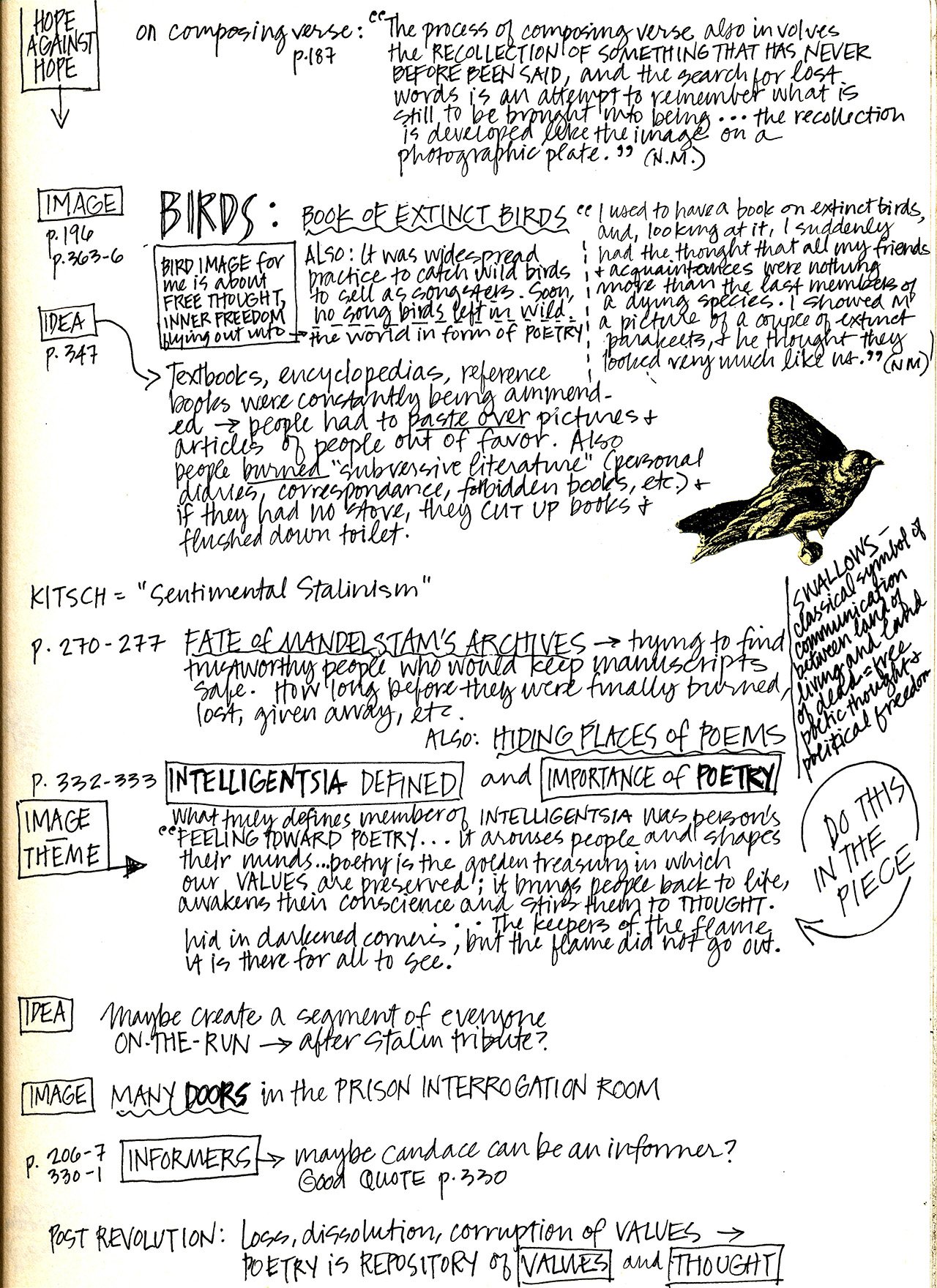

The KGB’s trademark predawn knock at the door provides a kind of pulse for The Akhmatova Project, developed by Keystone in collaboration with her 12-member ensemble (portraying nearly 40 characters) as a choreographed recital tracking the plight of poet Anna Akhmatova (Miranda Viscoli as the girl, Valerie Spencer as the woman) and her circle of mostly outcast artists.

The dance enlarges upon two major motifs. First, there’s the sheer reach of Stalin’s sadism—how for example, he lashed out at Akhmatova by repeatedly sentencing her only son, Lev (Joseph Grimm) to Siberian labor camps. Second is the fact that, in the Soviet Union, poets could be as influential, and disruptive, as today’s rock stars. That Stalin would sentence Osip Mandelstam (John Prosky) to hard labor for one poem is testament not only to Stalin’s paranoia and vindictiveness, but also to the high regard in which he held poetry. One line from the play— “There’s no place where more people are killed for [poetry]” — bespeaks a circumstance of history that many of our more serious artists might well envy.

The rest is largely a who’s who of Soviet lit, a roster of talent that includes Vladimir Mayakovsky (Christopher Kelley), Boris Pasternak (Eric Marx), Aleksander Blok (Russell Edge), Sir Isaiah Berlin (Grimm again) and even the ghost of Aleksandr Pushkin (Joe Palmiotti), with additional poetry and text by Joseph Brodsky, Nikolai Bukharin and Keystone.

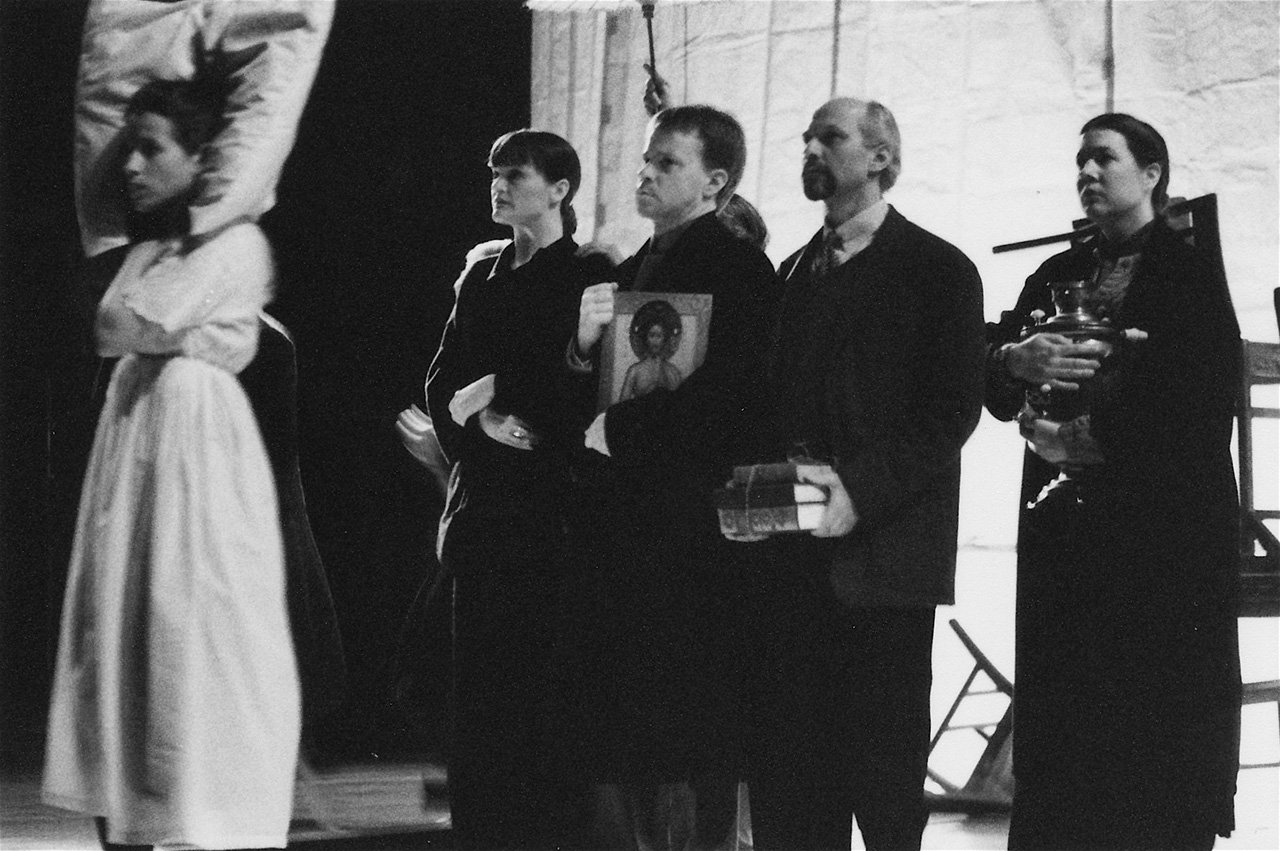

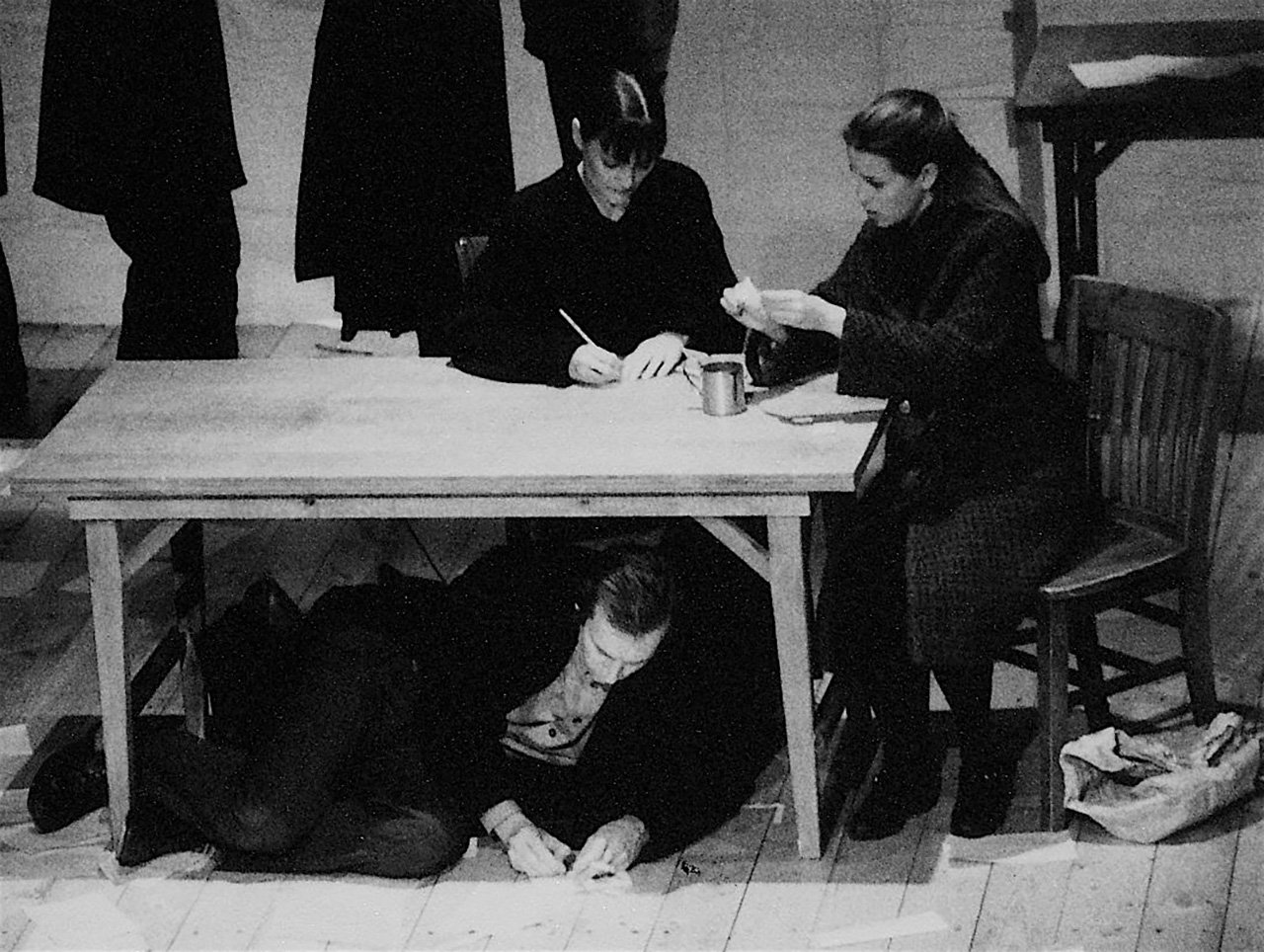

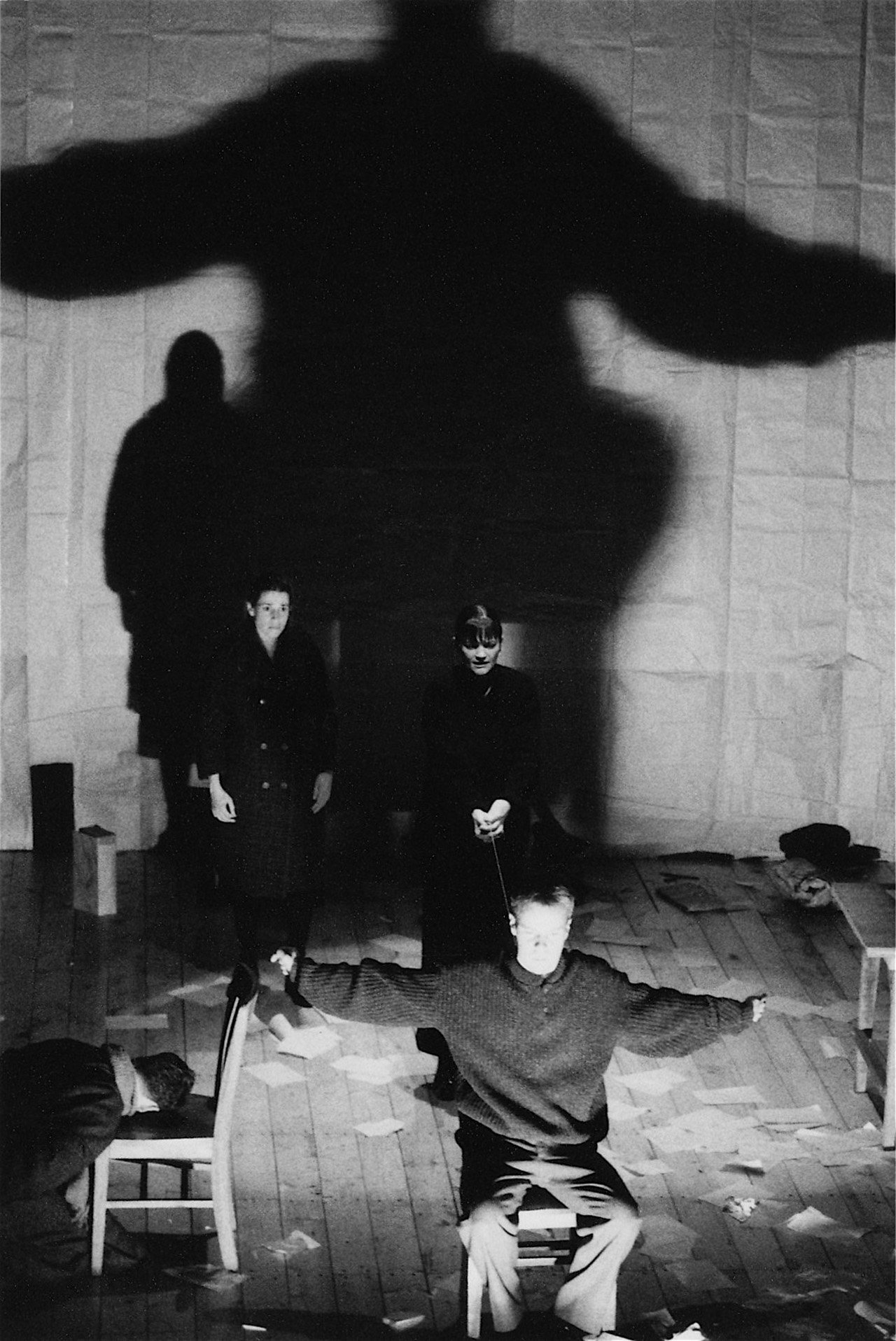

The Akhmatova Project’s literary ballet plays out on a mostly bare wooden stage, a feast of visual tableaux and symbols. Young Akhmatova slips out of a white dress to don the black dress of her maturity. Meanwhile, in a crescendo of terror and doom, most of her colleagues either are swept away or cut their losses and run to Paris. Mayakovsky, favored by Stalin, commits suicide. A scene depicting the march of citizens to the Soviet anthem, the Red Flag unfurling around them, ignites feelings of both inspiration and alarm. A firing squad guns down an artist th the strains of Mozart’s Requiem.

The plays points are driven home not so much by the abundant poetry in the text as by Keystone’s staging, juxtaposed against Randy Tico’s haunting sound design and original music. The tone is like a sledgehammer pounding an anvil. When sparks fly, they are the words of the poems, often spoken in Russian by Natasha Basley. The Akhmatova Project is a labor of devotion whose integrity resonates from the stage. Keystone has been developing the piece over many years. (It premiered in ASK Theater Projects’ 1998 Common Ground Festival.) Diligently researched, it is nonetheless an emotional cry, a tone poem, an ode to the vigor of the crafted word and to the people who craft it.

LOS ANGELES TIMES

“Poetry of the Soul”

by Jana Monji

March 9, 2000

A young girl holds a cheap piece of paper to her forehead. She’s memorizing not just words, but history and a legacy of terror and courage. The poem she fervently repeats to herself has been banned. This isn’t a Ray Bradbury story; this is the USSR circa 1930s.

Using lyrical movement, poetry and overlapping dialogue on a minimalist set, Nancy Keystone has created and directed an intense, expressionistic theatrical piece that starkly portrays the tragedy of Russian poet Anna Akhmatova’s life in The Akhmatova Project, a Critical Mass production at Actor’s Gang Theatre.

Akhmatova is played by two actors: Miranda Viscoli as the young Anna, freshly naïve in a white cotton dress, and Valerie Spencer as the older, more sophisticated woman, chic in black. Spencer bears a striking resemblance to Akhmatova, with deep-set eyes above high cheekbones, gazing sadly under straight eyebrow-length bangs. As both past and future, they comment poignantly on each other’s scenes.

Akhmatova’s first husband, poet and adventurer Nikolai Gumilev (Joseph Grimm, who also plays their son, among other roles), loved her, but “he hated children crying, raspberry jam in his teeth, womanish hysteria. And he had married me,” Akhmatova declares.

Keystone illustrates the decadent life of St. Petersburg with effectively choreographed romps of changing romantic liaisons and the flirtatious groveling of hopeful men, humorously much too eager to please the prancing actress-dancer Olga Glebova-Sudeikina (Candace Reid).

This lively society starkly contrasts with the terror under Stalin, a time when “only the dead smiled, glad to be at rest.” As St. Petersburg becomes Petrograd, then Leningrad, Akhmatova’s friends flee, are killed, or commit suicide. Nikolai is executed. Her son and her third husband are arrested. She waits in line outside the prison.”

Not everything fits. Why actor Joe Palmiotti doffs his dark togs and showers—and which of his five roles he’s playing at that point—isn’t clear.

Yet hearing the words of these persecuted literati—both in translations into English and in the original Russian (spoken by Natasha Basley) – the passion, strength, and despair of those days becomes tangible.

The lines that say “more than any other art, poetry is a form of cultural education: and that “poetry is respected only in this country [Russia]” seem alarmingly true.

Using an elegant, spare style, with original music by Randy Tico and a lighting design by Daniel Ionazzi, Keystone has captured and distilled a strong woman’s voice, and in this collaborative effort, the company shows an admirably earnest dedication to wonderful words that Stalin tried to silence.

AMERICAN REPORTER “Poets Against the State” by T.S. Kerrigan

April 7, 2000

LOS ANGELES—Moving in the shadow land that borders both dream and memory, Nancy Keystone, who both wrote and directs this play, presents a vibrant stylized representation of an age when the artist was in conflict with the state and was, as a result, hard pressed to resist extinction.

Seen through the eyes of the poets of the period, totalitarianism and creativity were inevitably at odds. The question seems to be, in part, whether the artist’s gift can save him in such circumstances.

Anna Akhmatova (Valerie Spencer) lived through some of the greatest political ferment in history. Born in 1889, she was a witness to the decline of the Czars, saw the Russian Revolution and the rise of Lenin, and lived through the cruel years of Stalinism. During the worst days of the last period she was publicly denounced and spent considerable time in prison.

On the personal side, she mirrored the storms of these political events with a passionate and tumultuous life, including a number of affairs and three marriages, two of which ended in divorce. We see these events through her eyes and the eyes of her fellow poets, Osip Mandelstam (John Prosky), Vladimir Mayakovsky (Christopher Kelley), Marina Tsvetaeva (Sarah Luck Gossage) and Alexander Blok (Russell Edge), most of whom suffered greatly from Bolshevism before they died. Of these besieged contemporaries, Akhmatova was the only true survivor, and even she bore her scars until the end.

Under Keystone’s consummate direction and choreography, the play, which is built on a series of short scenes representing events in the lives of these poets, moves with sustained force and power from beginning to end, even while it is indirectly narrating a chaotic and confusing time in history.

The characters are skillfully delineated as part of the action. Nothing seems to have been left to chance in the telling. We, the audience, can’t help being mesmerized as we watch the main characters move from hope to despair, and in Akhmatova’s case, to a kind of resolution in the end.

Much of the text of this play is Akhmatova’s own poetry in English translation. Keystone makes sure the words come out of her actor’s mouths sounding like genuine conversation, whether those words are directed at other actors onstage or at the audience. Anything less would have made them as stiff as the most unwieldy verse dramas of the last century. It is to her credit as well that she does not let up on the fundamental underlying tension between the characters.

The large ensemble of actors is so uniformly good that it would be unfair to single individuals out. Along with those already mentioned, however, Joe Palmiotti, Miranda Viscoli, Candace Reid, and Natasha Basley must be mentioned. They have obviously all worked hard to create their characters.

The big stage at the Actor’s Gang Theatre makes an ideal playing space for them or for any show like this where it is necessary for the actors to be in constant movement. It also helps to have Randy Tico’s original music integrated into the action. The Akhmatova Project is, in the final analysis, a powerful study of the struggle of the artist against the state and the often appalling costs of that struggle. Theater doesn’t get any more compelling or meaningful than this.

Video